Archives Blog April 2021

Frances Taylor’s Eastern Hospitals and English Nurses, and some less well known perspectives on Crimean War nursing

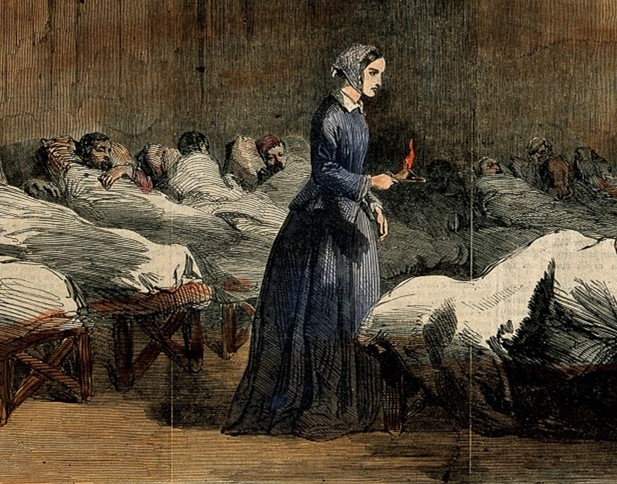

At this time of world-wide contagion, when so much depends on the ingenuity of medical researchers in developing vaccines and cures, and on the dedication of medical professionals in providing care, the name of Florence Nightingale is rightly honoured. Last year, the 200th anniversary of her birth, was designated by the World Health Organization as the ‘Year of the Nurse’. At the time when Miss Nightingale set out on her career to reform British public health provision, nurses were largely untrained, and were regarded as having the same social standing as servants. Her heroic efforts in reforming standards of care in the British army hospitals during the Crimean War, during which she obtained the famous epithet  ‘The Lady with the Lamp’ merely marked the beginning of her unceasing efforts in the sphere of sanitary and health reform.

‘The Lady with the Lamp’ merely marked the beginning of her unceasing efforts in the sphere of sanitary and health reform.

However, it is worth remembering that there were other women involved in Crimean War nursing, and that many of them also went on to have distinguished careers in the service of the public. A number of the nurses were the authors of memoirs, which give vivid insights into the lives of and work of many interesting and often relatively unsung women. One who has come quite fully into the public spotlight is the indomitable Mary Seacole, who was turned down when she applied to be part of the official nursing contingent, and who in 2004 was voted the ‘greatest black Briton’. A rather less well-known name is that of Elizabeth Davis, or more properly in her native Welsh, Betsi Cadwaladr, (shown right) whose autobiography was dictated to a skilled ‘ghost-writer’, the historian Jane Williams. Davis was a notoriously strong -willed and rather abrasive character, who famously refused to get on with Miss Nightingale. Nonetheless, the value of her contributions to the nursing service were later acknowledged by Miss Nightingale herself. The focus of historical accounts has understandably been on the work of Miss Nightingale and her party at the hospitals at Scutari in Turkey. But it is worth bearing in mind, as some historians have pointed out, that most of the nursing which was carried during the war took place independently of her, and was not necessarily performed according to her methods.

Davis, or more properly in her native Welsh, Betsi Cadwaladr, (shown right) whose autobiography was dictated to a skilled ‘ghost-writer’, the historian Jane Williams. Davis was a notoriously strong -willed and rather abrasive character, who famously refused to get on with Miss Nightingale. Nonetheless, the value of her contributions to the nursing service were later acknowledged by Miss Nightingale herself. The focus of historical accounts has understandably been on the work of Miss Nightingale and her party at the hospitals at Scutari in Turkey. But it is worth bearing in mind, as some historians have pointed out, that most of the nursing which was carried during the war took place independently of her, and was not necessarily performed according to her methods.

As is well known to those familiar with the life story of Venerable Mother Magdalen Taylor (or plain Frances Taylor as she was then), her own traumatic period as a Crimean war nurse also marked a defining crisis and watershed in her life and career. It was whilst nursing there that she converted to the Catholic faith, strongly influenced by the example of the nurses from the Sisters of Mercy and the French Daughters of Charity, whom she greatly admired, and the faith and resilience of the predominantly Catholic Irish soldiers who made up a large proportion of those whom she was nursing. It is often overlooked in popular accounts of the Crimean War that many of the nurses were Catholic or Anglican religious sisters.

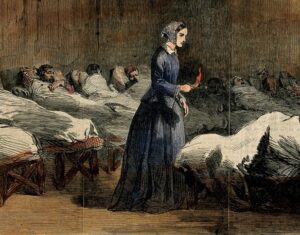

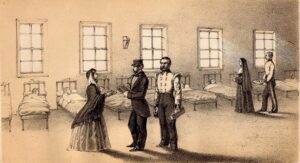

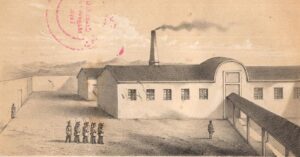

Mother Magdalen’s nursing experiences also led directly to the writing of her first book. The first edition of her Eastern Hospitals and English Nurses came out in a two volume edition in March 1856, just a few months after her return from Turkey. It appears to have been only the second published first-hand Crimean nursing account to appear. The illustrations to the right and below are from the book, and portray the hospitals at Koulali, a few miles from Scutari, where Mother Magdalen spent most of her time as a nurse. The book received extremely favourable notices in the press, which presumably justified the publication of a third cheap (revised) edition only ten months after its initial publication.

Mother Magdalen’s nursing experiences also led directly to the writing of her first book. The first edition of her Eastern Hospitals and English Nurses came out in a two volume edition in March 1856, just a few months after her return from Turkey. It appears to have been only the second published first-hand Crimean nursing account to appear. The illustrations to the right and below are from the book, and portray the hospitals at Koulali, a few miles from Scutari, where Mother Magdalen spent most of her time as a nurse. The book received extremely favourable notices in the press, which presumably justified the publication of a third cheap (revised) edition only ten months after its initial publication.

This was just the beginning of Mother Magdalen’s very dedicated but frequently overlooked career as a pioneer woman journalist, translator and editor, all of which work was offered up to the Catholic Church. Her work rate was quite astonishing when one considers its context in a life given over to the active work of a dedicated philanthropist, religious founder and superior-general. One story is that during her final illness she described to the nurse caring for her the time in the Crimean hospitals when she awoke to find rats running over her face, and the resultant sleepless nights which she had suffered throughout her life. It has been speculated that many of her voluminous writings were in fact produced during these dark watches of the night. As with many of her subsequent literary works, the book was written under a pseudonym (‘A Lady Volunteer’), and the spirit of self-effacement which it evinces was not lost on contemporary observers.

This was just the beginning of Mother Magdalen’s very dedicated but frequently overlooked career as a pioneer woman journalist, translator and editor, all of which work was offered up to the Catholic Church. Her work rate was quite astonishing when one considers its context in a life given over to the active work of a dedicated philanthropist, religious founder and superior-general. One story is that during her final illness she described to the nurse caring for her the time in the Crimean hospitals when she awoke to find rats running over her face, and the resultant sleepless nights which she had suffered throughout her life. It has been speculated that many of her voluminous writings were in fact produced during these dark watches of the night. As with many of her subsequent literary works, the book was written under a pseudonym (‘A Lady Volunteer’), and the spirit of self-effacement which it evinces was not lost on contemporary observers.

The book is essentially a detailed and vivid chronological account by Mother Magdalen of her nursing experiences, combined slightly uneasily with some colourful and occasionally humorous descriptions of local individuals and sights. The latter were perhaps intended to appeal to the wider readership for exotic travelogues. But Mother Magdalen’s beautiful and erudite account of the sights and sounds of Constantinople are worthy of cherishing, and characteristically they included a visit to assess the efficiency of the French military hospital at Pera. The main narrative combines moving accounts of the sufferings of individual patients, and the squalid and dangerous conditions in which the nurses had to work, with an incisively argued critique of the overall administration of the military hospitals.

The third edition of Eastern Hospitals (whose author is shown right, in her nursing uniform), ends with an impassioned plea for the improvement of the hospital system as a whole, based on the Christian ideal of self-sacrifice which she had so admired in her observation of the work of the religious sisters in the military hospitals. Its tone is also rather more trenchant than the previous edition, and it is noticeable additionally for its inclusion of statistics to strengthen its thesis. Those who wish to know more about these significant changes would do well to look at the detailed analysis produced by the late Sr Eithne Leonard, available in the SMG congregational archives. I would make one observation however, which is that Mother Magdalen’s figures for the death rates at Koulali hospital do not seem to have been noticed even by that distinguished statistician Miss Nightingale, in her thorough discussion of the data in her famous Notes on Hospitals (London, 1859) which only publishes partial figures. Am I the only one to have noticed this detail?

(whose author is shown right, in her nursing uniform), ends with an impassioned plea for the improvement of the hospital system as a whole, based on the Christian ideal of self-sacrifice which she had so admired in her observation of the work of the religious sisters in the military hospitals. Its tone is also rather more trenchant than the previous edition, and it is noticeable additionally for its inclusion of statistics to strengthen its thesis. Those who wish to know more about these significant changes would do well to look at the detailed analysis produced by the late Sr Eithne Leonard, available in the SMG congregational archives. I would make one observation however, which is that Mother Magdalen’s figures for the death rates at Koulali hospital do not seem to have been noticed even by that distinguished statistician Miss Nightingale, in her thorough discussion of the data in her famous Notes on Hospitals (London, 1859) which only publishes partial figures. Am I the only one to have noticed this detail?

Though her concern for the reform of the hospital system parallels many of the concerns of Florence Nightingale herself, there are considerable divergences of outlook based on Mother Magdalen’s particular perspectives and experience. Part of her intention in the book was clearly to defend the work of the religious sisters, and the administration of the hospitals at Koulali by Mary Stanley and her successor Miss Hutton, which had come under criticism. Along with Elizabeth Davis, she made it clear that she regarded the Sisters of Mercy overall as the most effective nurses in the English hospitals, and she had a particular admiration for the leader of the Irish Sisters of Mercy, Mother Francis Bridgeman. Her whole perspective in the book is to point away from herself and towards the achievements of others. If that has led to the relative neglect of her book as a historical source, perhaps this moment, when we are so dependent on the self-sacrificing spirit of dedicated nurses such as Mother Magdalen, is a good moment to reassess it as a historical source.

Paul Shaw

Florence Nightingale, detail from coloured engraving, 1855. Reproduced courtesy of the Wellcome Institute, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

Picture of Betsi Cadwaladr from her autobiography, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Frances Taylor, photography by Geremy Butler.