Archives Blog October 2019

Venerable Mother Magdalen Taylor and her connection with St. Winefride’s Well

Holywell in North Wales (in Welsh Treffynnon), must surely be one of the most fascinating and beguiling pilgrimage sites in the British Isles, the nobility of the architecture of the shrine and related buildings only being matched by the sylvan beauty of its setting. In this post I am going to say a little about Mother Magdalen’s devotion to St Winefride, and how it came to be reflected in what was probably one of her most popular, though now little known literary productions.

St Winefride’s Well at Holywell has been a continuous site of pilgrimage since the seventh century. But the life of its titular saint is shrouded in the mists of antiquity. According to the picturesque legend on which her reputation for sanctity is based, Winefride (in Welsh, Gwenfrewi) was a noblewoman who lost her life thwarting the attentions of a cruel and importunate suitor. But she was miraculously restored to life by her uncle and mentor, St Beuno. She later went on to become abbess of a convent at Gwytherin, some thirty miles away. Her spring of healing water is said to have leapt up from the very spot where she was martyred, a powerful symbol of grace and balm flowing from the rejection and defeat of violence, lust and cruelty.

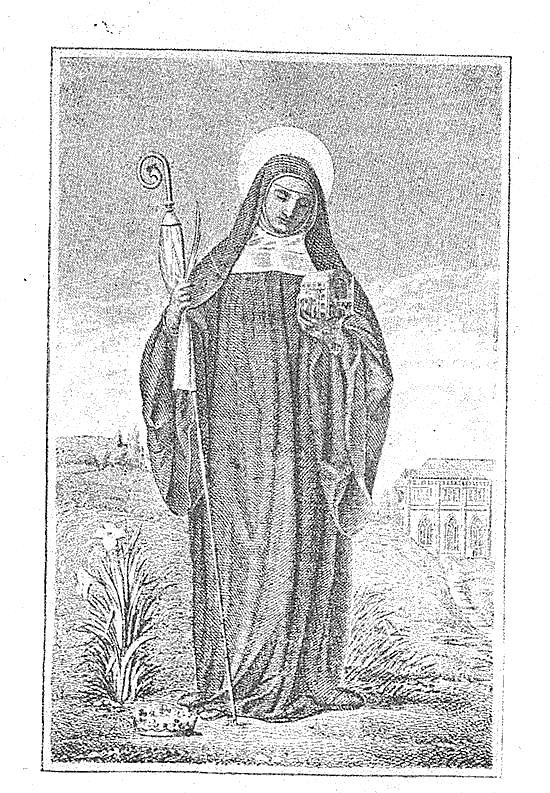

The beautiful engraving of St Winefride (right) from Mother Magdalen’s book depicts her haloed as a saint, and in the habit of a nun, carrying in her right hand the crozier of an abbess and what appears to be the palm of martyrdom. She is in meditative pose, and to her right are a crown and perhaps lilies, probably reflective of her purity and sacrifice of status in becoming a religious. In her left hand she seems to be holding her own reliquary shrine, whilst in the background is the chapel and well chamber at Holywell. This beautiful chapel, with its elaborate late Gothic canopy over a large pool of living water, and fine upper storey next to the ancient parish church, was remarkable for its virtually intact survival throughout the Reformation period. Miraculous cures were reported throughout the history of the site, attributed to the intercession of the saint, and reports of healings continue to this day. The first ‘lives’ of St Winefride were not written until the twelfth century, with the transfer of the saint’s corporeal relics to Shrewsbury Abbey.

Mother Magdalen’s own little book, St. Winefride or Holywell and its Pilgrims reflected the renewed interest and devotion to the saint and her shrine during the nineteenth century, as an increasingly confident British Catholic population sought to rediscover and celebrate its traditions and history. This was a process to which Mother Magdalen’s now frequently overlooked literary works made a very important contribution. The book was written early on in her literary career, shortly after her authorship of her first and most popular work of fiction Tyborne, and who went Thither (1859), and a couple of years before she became editor of the popular Catholic journal The Lamp.

The first edition of Mother Magdalen’s work is undated, but the date of 1860 has been established from the catalogue of the British Library and through other evidence collated by Alison Quinlan. Mother Magdalen may have first visited Holywell in order to pray for her niece, also named Winefride, who tragically died as baby in the same year. Mother Magdalen’s name does not appear on any editions of the work –a reflection of her famous humility – (she is simply given as ‘The author of Tyborne’) – but thanks to research by Mr. Tristan Gray Hulse, an authority on the well, we know that the book went through at least four editions, the final heavily revised edition being published as late as 1922.

Despite being little longer than a pamphlet, the book was evidently the product of careful research into the published material on the saint, and its popularity amongst pilgrims to the site is certainly reflected in its longevity! It even had the dubious accolade of receiving a published riposte in the form of a hostile parody by a local Protestant, Theophilus George Owens, entitled The Worship of St Wenefride; or Holywell and its Pilgrims, reflective of the prejudices which Mother Magdalen was most concerned to overcome.

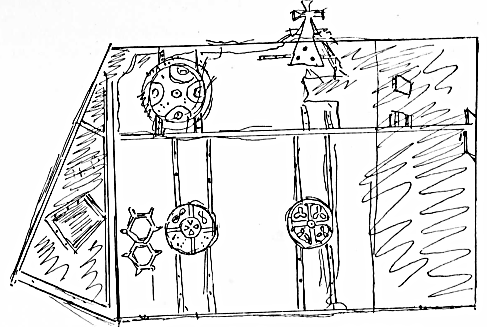

Moreover, references in Mother Magdalen’s book allowed Mr. Gray Hulse to locate a surviving fragment of a reliquary of the saint in the presbytery of St Winefride’s church in Holywell, as documented in a fascinating article co-written with the archaeologist Professor. Nancy Edwards (Antiquaries Journal, vol 72, 1992). The reliquary as it appeared in the seventeenth century is shown in the above sketch by the antiquarian Edward Lhuyd (from Parochialia ed. R. H. Morris, London, 1909-11). Its survival and identification – even as a fragment – represents a very important addition to the scanty evidence for Welsh decorative work of the period, and it has even been suggested that the reliquary is the earliest surviving material evidence for the formal veneration of any Welsh saint.

Another interesting connection between Mother Magdalen and Holywell is the vibrant and colourful stained glass showing St Winefride and St Beuno in the gatehouse chapel at Holywell, which is based on a charming but sadly anonymous illustration (above, right) taken from The Lamp during the period that she was editor (April 16, 1864).

There are six ancient churches dedicated to St Winefride, but with the great revival of devotion to the saint– in which Mother Magdalen and her friend Lady Georgiana Fullerton both played an important role – more churches came to be dedicated to her, and she came frequently to be depicted in ecclesiastical statuary and stained glass. I have included here two very fine but perhaps lesser-known effigies of the saint, both highly contrasted.

The noble statue of the saint depicted left is in St Marie’s Cathedral, Sheffield, a handsome Victorian Gothic revival building. She constitutes the most prominent feature of a beautiful side chapel in the chancel of the church, replete with images of female saints and religious. In contrast, the smaller image (right) is the focus of a similarly placed chapel in the elegant Edwardian classical-style church of Our Lady of Loreto and St Winefride at Kew Gardens, west London. Mother Magdalen would no doubt be very gratified to know of this dedication to one of her favourite saints so near to her own English home at St Mary’s Convent, Brentford, where there is currently a small temporary exhibition devoted to St Winefride. I am very grateful to both churches for permission to reproduce these photographs of their beautiful devotional statuary.

Paul Shaw