Archives Blog March 2019

The SMGs and the Great War (1914-19): The work of the Providence Hospital, St. Helens, Lancashire

Since 2014, the media and institutions at every level of British society have been concerned to memoriaise the centenary of the Great War, which has had such a powerful and abiding impact on the popular consciousness. That determined peace campaigner, Pope Benedict XV, referred prophetically in 1914 to modern nations ‘well-provided with the most awful weapons modern military science has devised [who] strive to destroy one another with refinements of horror.’ The other side to this desolate picture is the heroic sacrifice of those who laid down their lives, and also the contribution of those who sought to use the resources of civilisation to heal the minds and bodies of those ravaged by war. The SMG congregation has already published a tribute to one of those lives sacrificed to the war, Alison Quinlan’s heartfelt and beautifully written and researched tribute to Second-Lieutenant Edward ‘Eddie’ Dean RGA (1897-1916), produced as a booklet in March 2015. ‘Eddie’ was the great-nephew of the SMG founder, Venerable Mother Magdalen Taylor, and his young life was poured out, along with one and half million others –on both sides of the conflict –during the terrible Battle of the Somme in 1916.

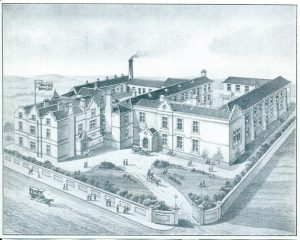

The Providence Hospital, St Helens, in 1909

We are now approaching the end of this great renewed period of public remembrance –for the armistice when the guns finally fell silent was in November 1918 and the centenary of the formal end of the war will fall in June of this year It thus seemed appropriate to examine more closely the contribution of the SMGs to binding up the wounds caused by the conflict, both literally and metaphorically. Alison in her book referred to the role played by Mother Magdalen Aimée (1865-1954), the niece of Mother Magdalen Taylor, in comforting Eddie’s mother ‘Georgie’ in her grief. It would take a greatly sustained period of study and research to produce any account of the contribution of the Sisters – individually and collectively – to the assuaging of the suffering caused by the Great War. It does seem appropriate at this time, however, to touch on just one of the more public ways in which the SMG congregation contributed, both practically and spiritually, to the binding up of the wounds caused by the war: the work of the Providence Hospital in St Helens.

Sources on the history of the Providence Hospital

The founding of the hospital may be said to have been one of Mother Magdalen’s most notable achievements. Soon after the arrival of the Sisters, she saw that the most essential need was for a free hospital to serve the heavily industrialised town. The Providence Free Hospital was founded in 1882, and until 1948 was run on a purely voluntary basis in terms of funding. Its closure in June 1982, due largely to re-organisation within the NHS, is still regretfully remembered by local people as the ‘day they shut the Prov’. Those wishing to know more about the early history of the hospital would do well to read some of the very valuable published academic work by Dr Carmen Mangion. Carmen has particularly emphasised the way in which the hospital had a particular vocation to serve working class women and children, always a great concern of Mother Magdalen Taylor.

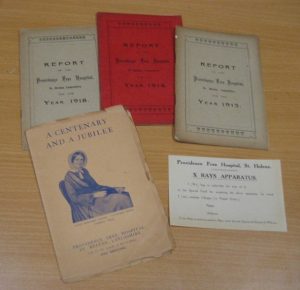

On the outbreak of the First World War, the managers of the hospital saw the need to respond urgently to the crisis. We are fortunate, in documenting this period, that a very rich archive survives for the hospital, including photographs, minutes of the hospital committee, and printed annual reports. There was also a very valuable short history of the hospital produced in 1932, ‘A Century and a Jubilee’, celebrating both the centenary of Mother Magdalen’s birth, and the fifty years since the founding of the hospital. It is recorded there that the ‘Prov’ was one of the first hospitals to offer its facilities to the military authorities. By May 1915, it was recorded that out of 1,088 patients treated in the past year, 54 were members of the armed forces, of whom 32 were still in the hospital. The hospital Sisters expressed their gratitude in the report that they had ‘been able to be of service in nursing the Soldiers’ but also said that they ‘heartily desire to be enabled to do more’.

The swift translation of this aspiration into practical results was reflected in the determination of the hospital committee to obtain X-Ray equipment, due to its perceived efficacy in helping to treat battlefield wounds. A slip was included with the 1914 annual report inviting donations towards this equipment. By 1916 it was recorded that the apparatus had been acquired at a cost of £300.In the same report, the Sisters made an analogy with the work of Mother Magdalen Taylor, saying:

Soldiers’ Ward, 1914-1917

‘…it cannot but be a source of special gratification to them that this Hospital…should be of some small service to wounded soldiers, and also to Volunteer Nurses, as it may be considered that [Mother Magdalen’s] career of active charity…began in a special way when as a Lady Volunteer nurse she joined Miss Nightingale’s band to nurse the wounded soldiers at the time of the Crimean War.’

The following statement was included in the hospital annual report for the year 1918:

‘…Altogether nearly 1,000 members of His Majesty’s Forces passed through the Military Ward, and it is gratifying to know that the kindly care, attention, and services rendered by the Sisters and Nurses have been so warmly appreciated by the patients, and have also received the commendation of the War Office authorities. It has been decided to erect in the Main Corridor of the Hospital a Tablet commemorating the above facts.’

In March 1919 an official letter was sent from the War Office to the hospital superior, expressing the thanks of the Army Council for the ‘whole hearted attention and devotion’ of the hospital staff. However, a more moving –because more personal –tribute came from a Lt-Colonel Branan of the 64th West Lancs, who in the same month wrote offering to donate to the hospital his unit’s portable piano, at the urging of his men, virtually all of whom came from St Helens.

He concluded his letter saying:

‘…I know nothing of your Institute or your work, but if the St Helens boys who have served with me are specimens of what you do and can do, then I can say honestly that I want nothing better.’

It seems safe to presume that Mother Magdalen, whose tender regard for her military charges is a matter of record, would have greatly appreciated these sentiments.

Paul Shaw